Self-learned vehicle control using PPO

[video coming soon]

Context

This project was done as part of a contest in DD2438 Artificial Intelligence and Multi Agent Systems course at KTH.

We were given a Unity environment with 4 3D mazes and “realistic” car and drone models. The task consisted in creating an AI capable of navigating from start to finish of any maze as fast as possible.

We were the only team to address the challenge using a data-driven approach (RL) and achieved fastest accumulated times over all test (previously unseen) tracks.

Approach

We solve it combining two main ideas:

- Plan an approximate path running Dijkstra on the environment’s Visibility Graph. This returns a list of 3D points (checkpoints) which is then feeded to the controller.

- Use PPO (Proximal Policy Optimization) to learn a policy to follow this pre-computed path as fast as possible without crashing into walls.

Environment

In a nutshell:

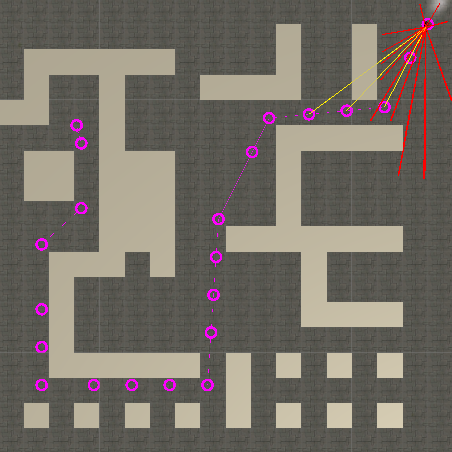

In pink the best path found by Dijkstra. The circled checkpoints are passed to the controller. The controller reads the relative position of the upcoming 4 (yellow lines from car to checkpoints). The red lines are the lidar ray-casts which inform the controller of the walls position.

Car action-space

- Throttle: Continuous value between -1 and 1. 1 translates into going forward at full speed and -1 braking or going backwards.

- Steering: Continuous value between -1 and 1 where -1 is turning left and 1 turning right.

State-space

- Next n checkpoints relative position: For the agent to learn what direction to go it is essential that it knows where the next n checkpoints are located w.r.t. itself. In order to efficiently drive through the maze it is critical to not only know the next checkpoint but also be able to anticipate and adapt the trajectory considering future movements.

- Relative velocity: To capture the current dynamic state of the vehicle, the agent needs to know its velocity, both in the forward direction and in the lateral(to understand when its drifting).

- ”Lidar”: These values represent the distance to closest obstacles for fixed directions in vehicle frame, simulating a lidar sensor without noise. Our tests show that an agent aware of its obstacle surroundings outperforms a blind one.

Reward system

- Reaching checkpoint: Latest trained models reward the agent with 1 point for passing through one of the checkpoints in its state checkpoint window. If it passed through a checkpoint more advance than the closest one, the reward also adds the sum of checkpoints in between. This is to enhance the agent to find optimal trajectories between checkpoint windows.

- Time: To guarantee that the agent learns to complete tracks as fast as possible we also add a negative reward for each time-step the agent is running in a given environment.

Learning process

We use curriculum learning in order to speed the training process. To do so, we sequentially generate random mazes of increasing driving difficulty (number of blocks). Once the agent is able to master a certain difficulty, it advances to the next level. The first levels do not have any walls and are completed simply by driving in a straight line.

The algorithm we used to train the policy is PPO (Proximal Policy Optimization): A policy gradient algorithm “simple” to implement and tune. More on it on this video.

Future work

Once the control is learned, it would be interesting to learn also the path planning. Following the curriculum learning approach, we could start by stretching the distance between key points until we only provide the goal. This could require of an RNN architecture so that the agent somehow remembers the traversed maze.

Takeaways

-

RL is hard. Current RL algorithms are far from being “plug and play”. This was our first approach on a (relatively) more complex problem and we were surprised by how much the state-action space, algorithm and meta-parameter choices affect the performance.

-

Work in relative coordinates w.r.t the agent. Otherwise the state-space can become too confusing. Including rotations also rise its dimensionality.

-

Do NOT over-engineer rewards! Its a huge temptation but defeats the whole purpose of RL. At a certain point you might as well just write an heuristic to solve the problem and save headaches.

-

Curriculum learning helps a lot. Specially with limited computing resources. Attempting to directly drive on complex mazes proved to be too slow to learn. Start with a very simplified problem and once it works, evolve from there.

-

Formal experiment design & tracking is super important (such as fractional factorial design). We spent around a week by intuitively (or randomly) trying things without getting it to work. It wasn’t until we stopped to think the best experiments to perform and formalized them in a spreadsheet that we started to consistently see good results. In later projects we automated these searches using Bayesian optimization.

Design choice justifications, experimental results, further detailed explanations and drone state-action space adaptations in the full report.